Oppenheimer has been a very divisive movie for those without baseline media literacy. Some are boycotting it because it doesn’t feature the Japanese people directly affected by the weapons of mass destruction that J. Robert Oppenheimer created, but I think it’s clear we’re seeing the world through Oppenheimer’s eyes and that indicates his lack of willingness to fully face the atrocity that he abetted. Others inexplicably believe it is government propaganda, which is a wild take on a movie that is explicitly about finding a way to live with yourself after doing something so objectively horrible that it has irreparably changed the course of history.

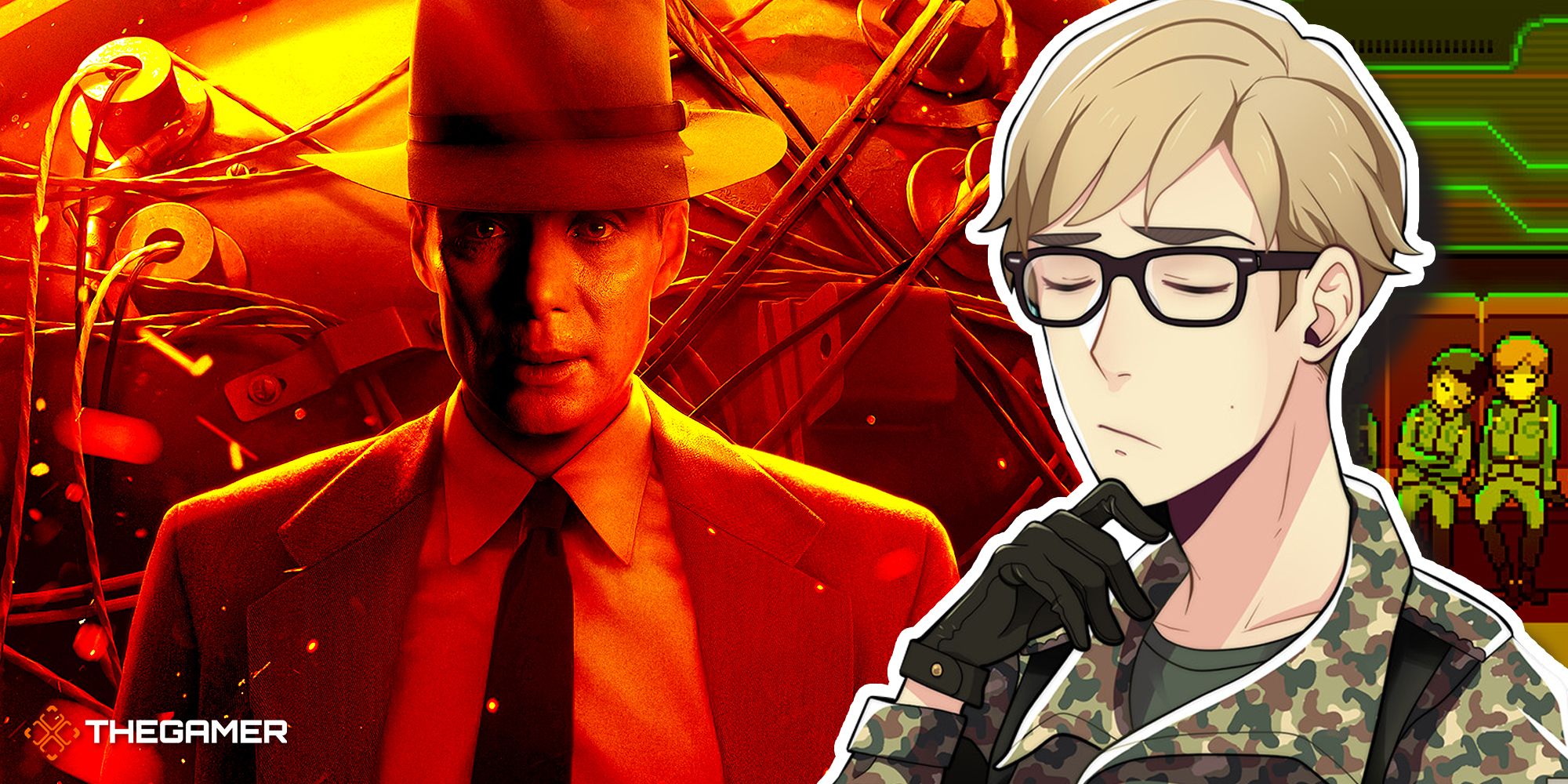

There’s also been comparisons of Oppenheimer to triple-A game releases, with a shortage of IMAX tickets, technical malfunctions like the film playing upside down, equipment failures, and huge amounts of unrelated discourse. That got me thinking – when was the last time a video game that treated war in this way was released? When thinking about video games involving war, Call of Duty immediately springs to mind, but I’m more interested in games that explicitly denounce war and the human cost that inherently comes with it. Call of Duty doesn’t qualify here. One might think about the Fallout series, Metal Gear Solid, Spec Ops: The Line or This War of Mine. But for me, that game is Long Gone Days.

I first discovered Long Gone Days in an itch.io Bundle for Racial Justice and Equality, which I bought in the early days of the pandemic as the George Floyd protests went on. It describes itself as a “modern-day RPG that imagines the world of war that's coming for us, with a focus on language barriers and the human cost of these conflicts”, which was immediately appealing to me, so I gave it a shot. What followed was a deeply touching, emotionally harrowing experience.

In the game, you play as Rourke, a young paramilitary soldier who is given the opportunity to showcase his skills on an important mission. He is sent to Poland, where he provides long-range support for his squad. He soon learns that The Core, the paramilitary organisation he is a part of, aren’t the good guys after all – he has just taken part in a false flag operation, killed unarmed, innocent civilians, and incited a war in the country he initially sought to protect. It’s an astonishingly heavy realisation, one that feels even weightier because this is a real country. The stakes are high, and in this game, the stakes are everything.

Rourke and a sympathetic medic, Adair, flee to a small Russian town after they learn what they’re really doing and are labelled traitors by The Core. The rest of the game unfolds from here, and it balances these recent events with turn-based encounters. Rourke and Adair only speak English, meaning they can’t understand the people who live there and have to find a translator. The story then largely revolves around Rourke’s escape and his desire to repent for the bad thing he’s done. Mechanics involve keeping party morale high, recruiting interpreters to communicate with different people, and turn-based battles.

This is a simplistic, very truncated description of a very thematically interesting game, but that’s because I haven’t returned to it in a while. Having been in Early Access for five years, and as of now still incomplete, the developers announced last week that they have finally partnered with a publisher to give them the resources to finish the game. I can’t wait – whatever I did play was resonant enough that years later, I still think about the game often and check if it’s been completed yet. Fingers crossed for a full release soon, but play the demo anyway. I’m not interested in media that glorifies war, which is why I loved both Long Gone Days and Oppenheimer, neither of which are military propaganda. I can’t say the same for Call of Duty.